*Scrollez pour la version française my friends *

So, let’s say it’s the early XX century. Let’s say it’s 1936 or so. And we’re in the cosy decorum of a British bourgeois home in London. It’s winter let’s say – we might be getting close to new year’s eve who knows - so we’re sitting by the fire. Facing us sits a man. He is in his early forties. Random face, good manners. I picture him thin and not very tall. Maybe his voice is low. Maybe he speaks with a lisp who knows. Anyways the man talks to us. Not any random mundane talk though: he is exposing one of his theories. One of the greatest he formulated in his lifetime actually, one that would make him world famous and send him straight to posterity. So, the man is passionate, he talks well, and we’re taken by his flow. And suddenly, we’re hit: his theory is about to change our lives for ever.

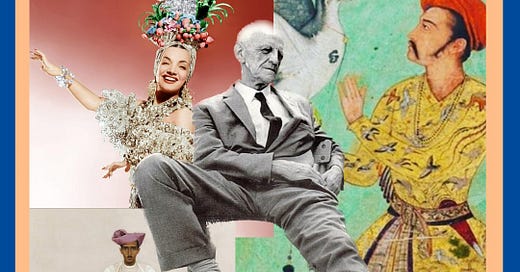

That man’s name is Donald Winnicott. He was a British paediatrician who contributed to the modern conception of parenting. And his genius theory is “the good enough parent”.

No no, I did not change the topic of this NL, we’re still talking professional fulfilment here, bear with me.

So “the good enough parent”. It’s so simple, it’s genius.

You don’t need to give it all you’ve got, every inch of your being and every drop of your soul.

Here it goes: for your child to be alright you don’t have to be the best parent on earth, let alone perfect. You don’t even have to be good! For your child to be alright, you have to be good “enough”. Ha! “Enough” meaning you do what’s necessary to fulfil your child needs. Like give them some friends, some food and a bed! (that’s not Winnicott, that’s me).

Of course, “good” is subjective. But the point here is: you don’t need to give all you’ve got, every inch of your being and every drop of your soul to your child for him or her to be a happy adapted being and turn into a functional adult. What a relief. If there are parents among you dear readers, I am sure you’ll agree.

If there are Winnicott’s disciples on the other hand, not sure you’ll be fond of this very personal interpretation of the man’s thought. Let’s just say this is my own take on his work.

Perfection is a delusion. It’s a broken compass. People don’t want perfection, they want progress. They want learning curve, they want “done”. So, let’s give them that instead.

And here is how I decided to translate it to the professional world for it to serve us all:

To perform at work, you don’t need to be the best, let alone perfect (yes, I am looking at you impostor-syndromers overachievers)! To perform at your job, you need to be good enough, meaning do what’s necessary to reach your goals.

You don’t need to give it all you’ve got, every inch of your being and every drop of your soul.

Very much the opposite.

Your skills and time are precious resources. Give your best to what serves you.

That’s a very common mistake, isn’t it. We believe that by giving our best, staying late, putting all our energy and intellect into what we are asked to do, we’ll get noticed. We’ll be rewarded, we’ll be liked! That this is the fastest, smoothest way to professional accomplishment, when it’s actually the highway to exhaustion.

Perfection is a delusion. It is a broken compass. The only person noticing is us and the potential credit will never match the amount of effort and skills we put in there. So, let’s drop it. People don’t want perfection, they want progress. They want learning curve, regular reports, they want to know what’s going on – even when it’s a difficulty or a doubt -, they want “done”. So, let’s give them that instead of a fantasied gift-wrapped perfection of a work that nobody will appreciate, and nobody asked for in the first place.

What really serves you on the other hand, is your strategy spirit.

At work, we deal with many different things: tasks, files, clients, etc.

Give your best to what serves you.

And for the rest, the routine stuff, let’s learn to put our minimum acceptable effort into it (aka MAE). Find that flotation line where the work you put in there is .just.enough.

Your skills and time are precious resources. Put them where you’re thrilled, where the perspectives are: that file that really interests you, that strategic project, that client with big budgets, that case that will make you meet interesting people (the cathedrals!), you name it.

Put them first, focus on them, spend more time on them, deliberately, give them that extra hint of creativity.

And for the rest, the routine stuff, let’s learn to put our minimum acceptable effort into it (aka MAE). Put them last, stick to what’s necessary, switch your standard to “alright / ok that should do it”. Find that flotation line where the work you put in there is .just.enough.

Oh, I know. It won’t be easy all the time. It may take some time to unlearn years of perfectionism (I feel you impostor-syndromers overachievers!).

But be assured: even with just that, your work will be just fine. It will be more, weigh more than enough.

And here we are back on our Winnicott’s feet!

I wish you a happy new year dear readers, see you on the other side!

Now, on your saddle, and off you go.

Clara

Et nous voici en French-speaking zone, enjoy!

Disons qu’on est au début du XXe siècle. 1936 disons. Et que nous sommes dans le très confortable décorum d'un foyer bourgeois à Londres. Disons que c'est l'hiver - nous approchons peut-être du réveillon du nouvel an qui sait - donc nous sommes assis près du feu. En face de nous se trouve un homme. Une quarantaine d’années, visage quelconque, bonnes manières. Je l'imagine mince et pas très grand. Peut-être que sa voix est basse, peut-être qu’il a un cheveu sur la langue, qui sait. Quoi qu'il en soit, il nous parle. Mais pas de banalités : il nous expose l'une de ses théories. L'une des plus importantes qu'il ait formulées au cours de sa vie à vrai dire, l’une de celles qui allaient le rendre célèbre et lui ouvrir les portes de la Postérité. Donc l'homme est passionné, il s’exprime bien, il nous emporte. Et tout à coup, on réalise que sa théorie est sur le point changer nos vies.

Cet homme s'appelle Donald Winnicott. Pédiatre britannique qui a contribué à la conception moderne de la parentalité. Et sa théorie géniale est celle du "parent suffisamment bon".

Non non, je n'ai pas changé le sujet de cette NL, on parle toujours d'épanouissement au travail ici, bear with me.

Donc, "le parent suffisamment bon". Si simple, si brillant.

Il n’est pas nécessaire de tout donner, la moindre parcelle de votre être, la dernière goutte de votre âme.

La voici : pour que votre enfant aille bien, vous n'avez pas besoin d'être le meilleur parent du monde, encore moins d’être parfait. Vous n'avez même pas besoin d'être un bon parent ! Pour que votre enfant aille bien, vous devez être « suffisamment bon ». Ha ! "Suffisamment" signifiant faire ce qui est nécessaire pour répondre à ses besoins. Des amis, de la nourriture et un bon lit ! (ce n'est pas Winnicott, c'est moi).

Alors bien sûr, c’est très subjectif. Mais l'idée est celle-ci: il n’est pas nécessaire de tout donner, la moindre parcelle de votre être, la dernière goutte de votre âme à votre enfant pour qu’il devienne un être heureux et socialement adapté.

Quel soulagement. S’il y a des parents parmi vous chers lecteurs, vous serez sans doute d'accord.

S’il y a parmi vous des disciples de Winnicott en revanche, je ne suis pas sûre que vous adoriez cet exposé très personnel de sa pensée. Disons simplement que c'est mon interprétation de son travail.

La perfection est une illusion. C'est une boussole cassée. Les gens se fichent de la perfection, ils veulent du progrès. Ils veulent une courbe d'apprentissage, et ils veulent du "c’est fait". Donnons-leur cela plutôt.

Et voici comment j'ai décidé de le transposer au monde professionnel pour qu'il nous soit utile à tous :

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Transgression by Clara Moley to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.